Jack Holly (Summer Fellow, 2023) discusses their path to photography and the portrait series they developed during their summer at Ox-Bow.

At age 18, Jack Holly bought their first camera and has ever since been entranced by what appears in the view lens. Through photography, Holly has captured everything from the landscapes of rural America to intimate glimpses of BDSM culture, at times even intertwining the two as seen in How to Steal a Plane. Their ongoing portrait series sits in thoughtful juxtaposition to their past career as a model. Ultimately, they were unsatisfied with their experiences in front of the camera. “It made me feel like a hat rack for other people,” Holly shared. This perspective deeply informs how they aim to render images of others. Their untitled project, which documents genderqueer and gender-nonconforming individuals through portraiture, prizes the autonomy and power of individuals. Through interviews with the subject and collaboration during the shoots, Holly hopes to capture their subjects in a way that honors and elevates.

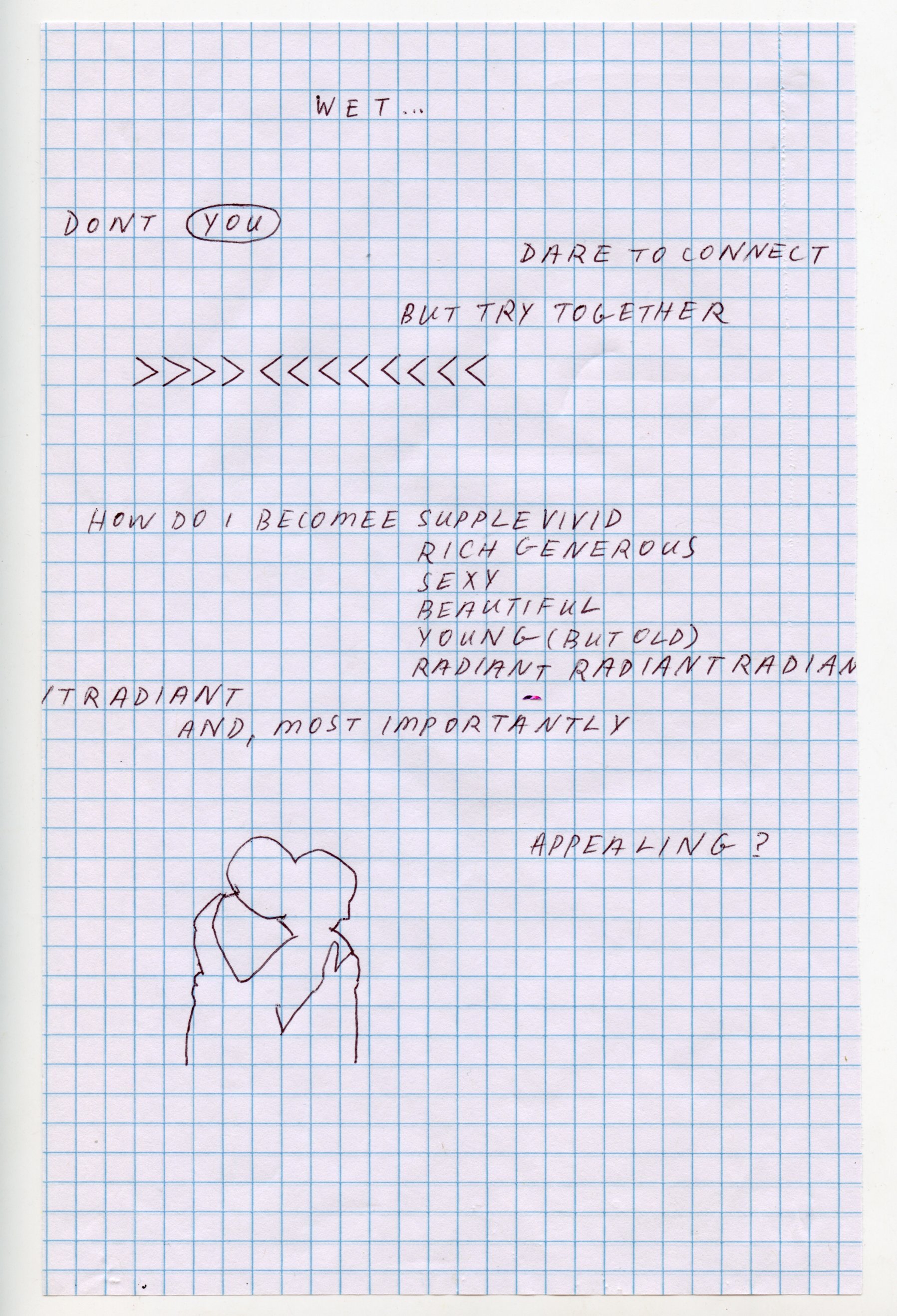

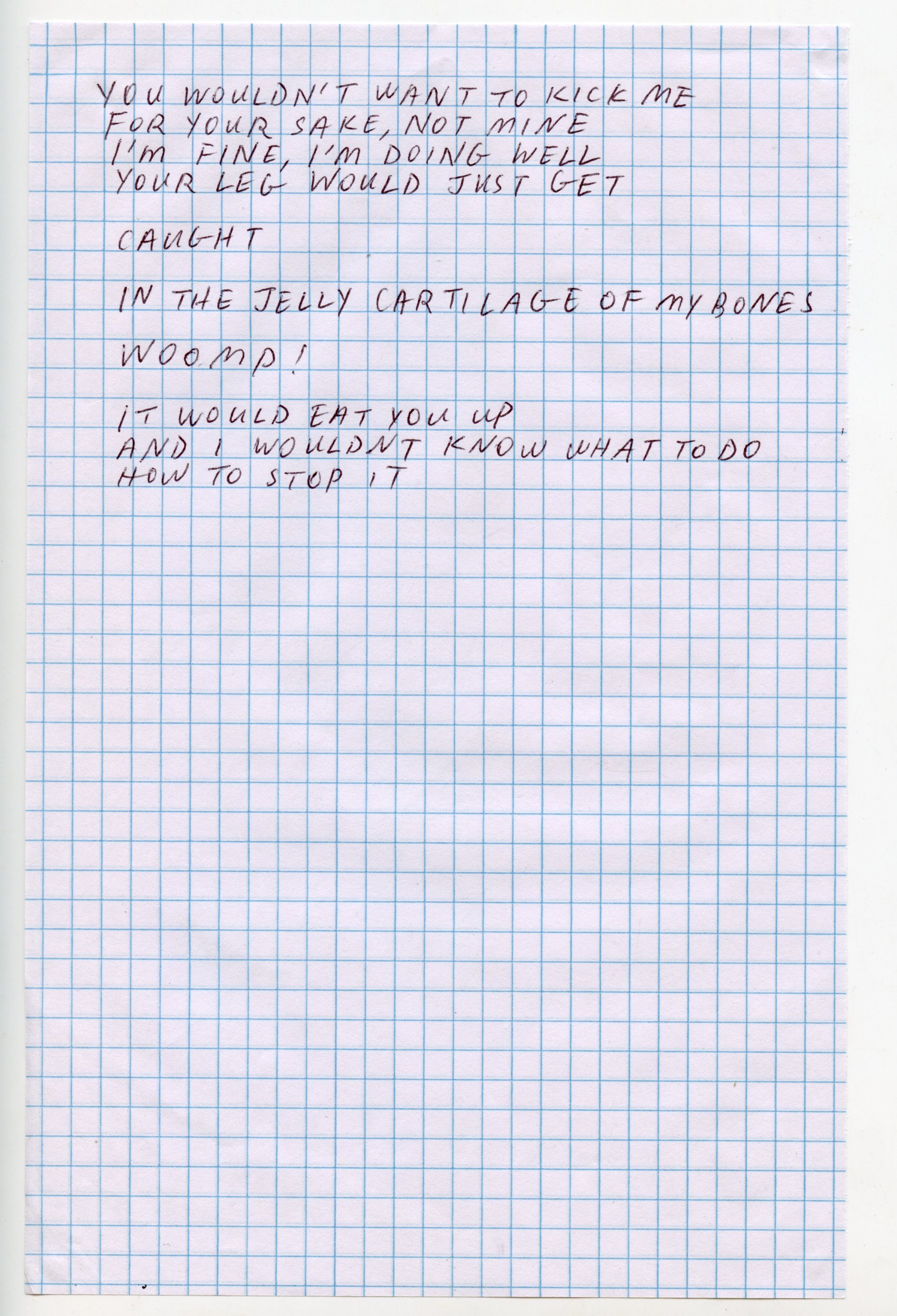

(left) A portrait of EXYL.

(right) A portrait of John Rossi. Photos by Jack Holly.

During the summer of 2023, after completing their BFA at the Kansas City Art Institute, Holly started their portrait series on campus where they spent 13 weeks as a Summer Fellow at Ox-Bow School of Art & Artists’ Residency. In each photo, an individual identifying as queer or gender nonconforming faces away from the camera and holds an object of meaning to them. “It's one of those projects that I kind of consider a sketchbook practice because it's not really a main tenet of my practice, but it's a way for me to continue photographing and getting to know people and understanding the weird part of people's lives,” explained Holly. During each portrait session, Holly incorporates an interview to better understand the individual. Oftentimes, the stories they reveal are deeply personal. “It's an honor that people feel so open,” Holly said.

Throughout their 13 weeks on campus, they continued taking photos and also ventured into another new project, a performance piece that would eventually become the short film “Big Yellow Horse.” The film’s inspiration took root in Holly’s long standing fascination with Dante’s “Inferno” and Holly describes their work as a “surrealist adaptation” of the text. Having first read the work at age 14, Holly said, “it was a pretty formative text growing up and… [I] always had it checked out at the public library.” Perhaps it is partially this childlike fondness that charges Dante’s themes with new relevance. “The dead have collected and keep my memories now. The world will go on without them,” serves as the film’s opening words. These two lines baptize viewers with the sense of existential modesty that guides them through the rest of the film.

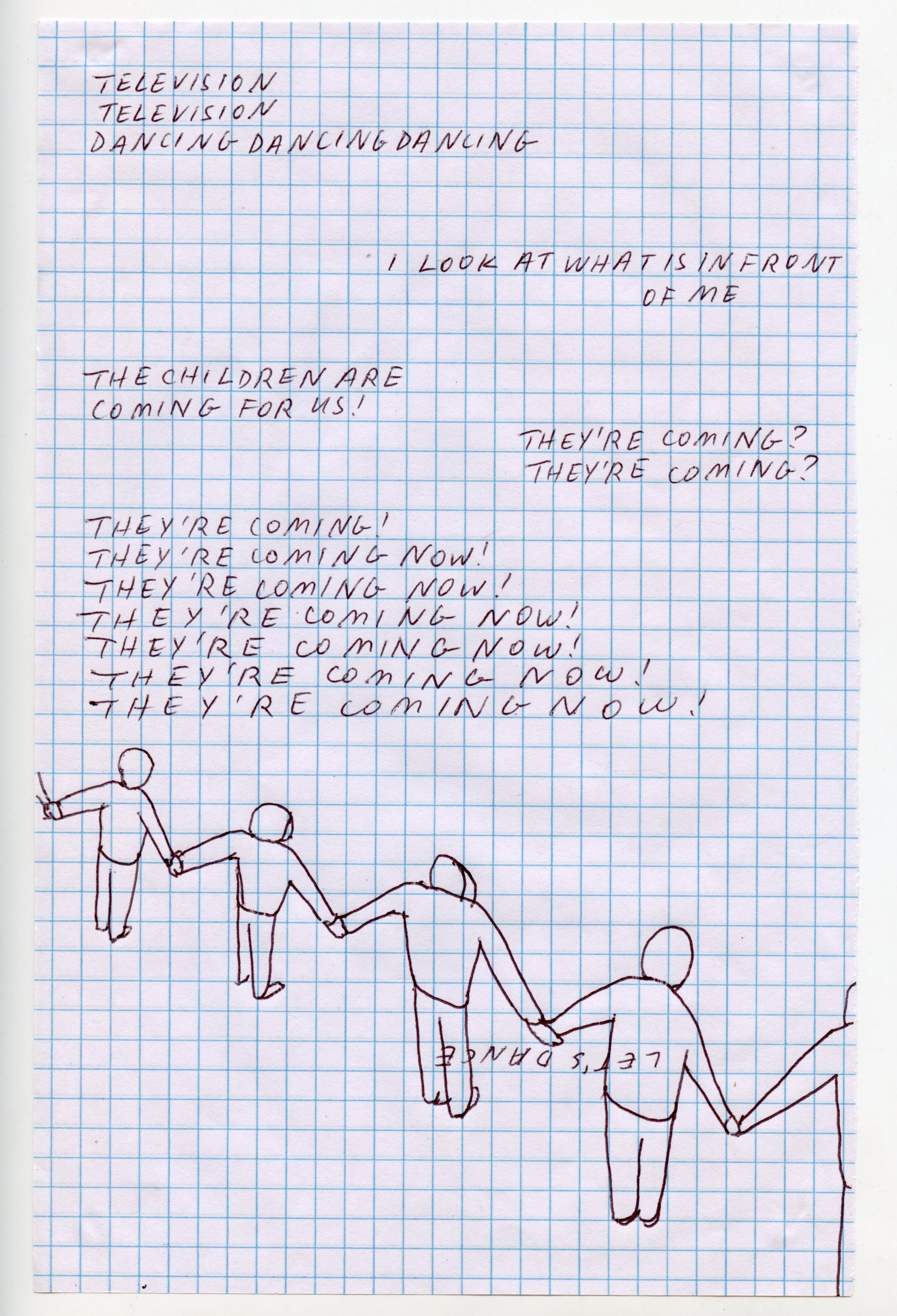

Still from Jack Holly’s short film “Big Yellow Horse.” Image courtesy of the artist.

Big Yellow Horse builds its own language and logic, creating a world for its audience. Though the piece only runs for six minutes and twenty-some seconds, Holly creates a universe that tugs at the threads of death and memory, weaving them into a visual oasis. The word inferno doesn’t easily come to mind amidst the shots in which Cole Bespalko floats on an air mattress on Lake Michigan's water, but Holly isn’t aiming for simple, as is evident through the psychedelic editing style and sound design that wavers between transcendent and terrifying, like the film’s many symbolic coin flips and flickering lights. While others may have been tempted to manifest inferno with more depictions of brimstones and damnation, in Holly’s hands “Big Yellow Horse” presents downfalls as an opportunity for inferno to function as rebirth, akin to a phoenix gifted with the liberty of a tabula rasa.

In creating the film, Holly was eager to involve other artists on Ox-Bow’s campus. A number of other summer fellows joined the film as actors. Artist and LeRoy Neiman Fellow EXYL consulted on sound design and staff member Michael Stone wrote the poem that opens the film. The process of filming held its own adventures including late night shoots and on one occasion, Holly fell into the lagoon while trying to capture the perfect shot. At each moment, Holly emphasized the warmth the community offered, whether that included volunteering to help during the witching hours of campus or laughing alongside them when they took their unintended dip. The film’s private debut was also communal; it first aired on the meadow during a 10 p.m. screening in which staff, students, faculty, and other artists gathered together. After its private showing at Ox-Bow, “Big Yellow Horse” made its public debut at the Glenwood Arts Theatre in Kansas City.

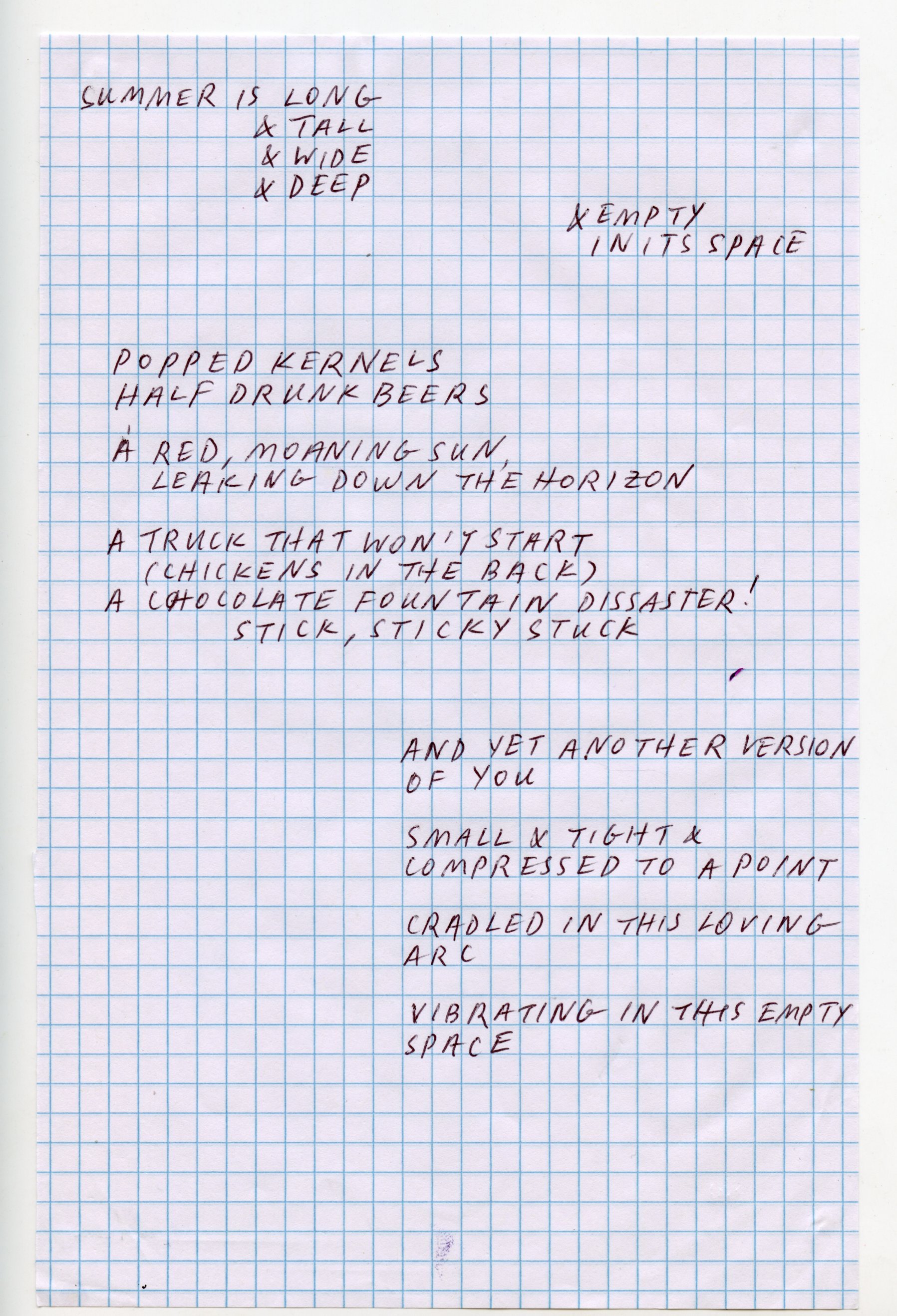

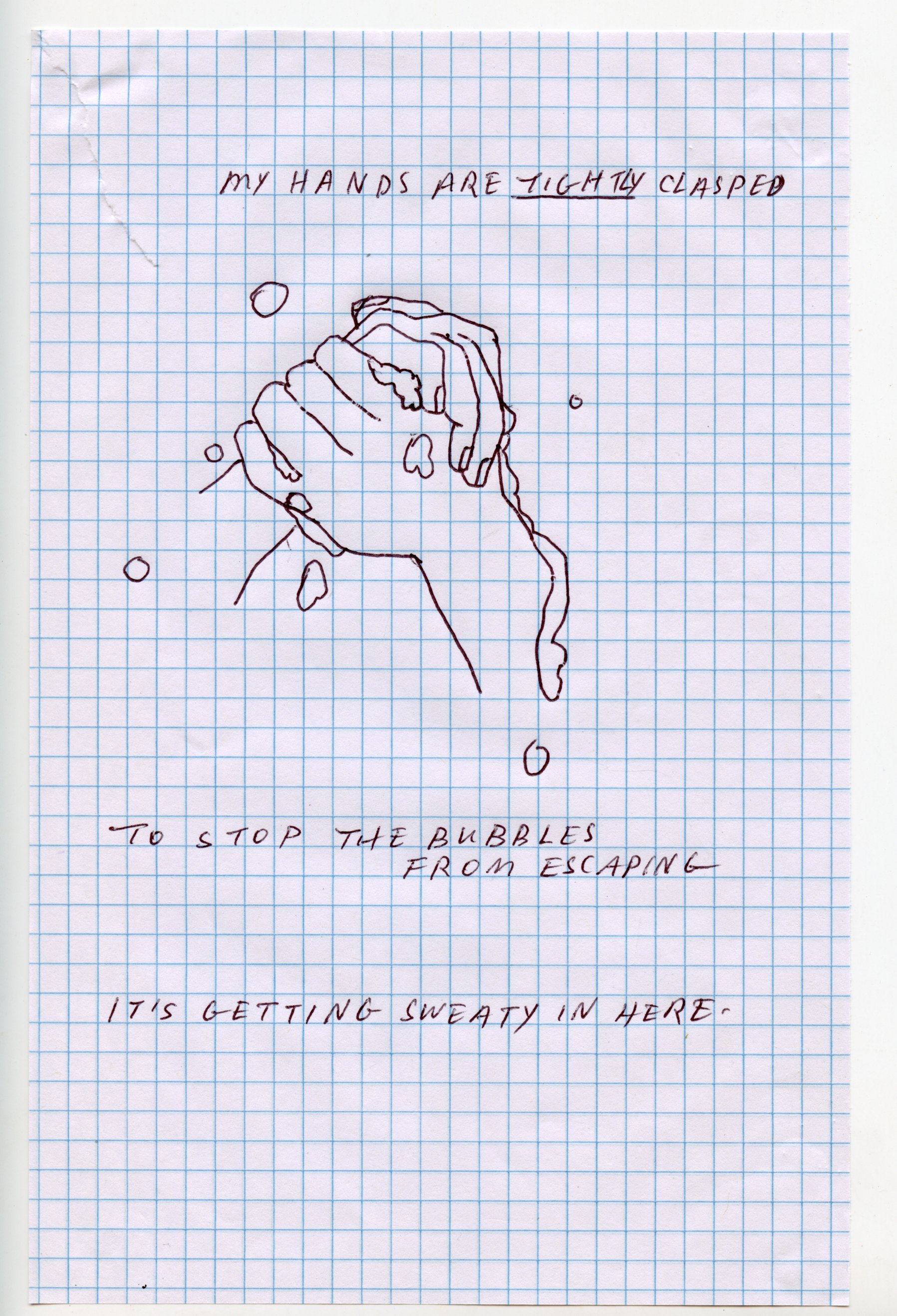

(left) A Portrait of Aidan Mudge.

(right) A Portrait of Cole Bespalko. Photos by Jack Holly.

Since the conclusion of Holly’s fellowship, they have settled into their post-graduate life in Kansas City. While working full time at a frame shop and gallery alongside keeping up a studio practice has not been without challenges, they still manage to get into the studio most days and have continued the portrait series they started at Ox-Bow. Nowadays, Holly photographs people in their own homes. “It can be intimidating because I'm a tiny person, and you never know what someone's gonna do when you meet them on the internet,” Holly acknowledged. “It's a really weird exchange of trust and intimacy,” they added, an exchange that has cultivated a captivating series of images.

For the foreseeable future, Holly hopes to continue developing short films, rendering photographs, and spending time with their family and new niece.

This article was written by Shanley Poole based off interviews conducted with Jack Holly in August 2023 and February 2024.